Despite the encouraging ecosystem and scheme, supply order of only 61% of the initial target of electric buses has been issued after three years of the FAME II scheme. The actual number of electric buses running on roads under FAME II is even less than 30% of the buses tendered. This article by UITP India provides an in-depth look at the current scenario

The electric bus market in India received a boost of budgetary support of Rs 10,000 crore through the subsidy scheme of Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicle (FAME II) in 2019 with 5,595 buses approved across 64 cities (1). More than 90% of the sanctioned buses will cater to urban demand. At present, the supply order for 3,428 buses has been issued and 865 buses have been deployed under FAME II across various states (2). Despite the encouraging ecosystem and scheme, supply order of only 61% of the initial target of electric buses has been issued after three years of the FAME II scheme. The actual number of electric buses running on roads under FAME II is even less than 30% of the buses tendered.

Unlike FAME I wherein a state transport undertaking (STU) could adopt the business model of outright purchase or gross cost contracting (GCC), FAME II has restricted it only to GCC (3). In the outright purchase contracts, the buses were supplied with an option of providing annual maintenance contract (AMC) along with charging infrastructure for definite period as mentioned in the released tender. In GCC, the scope of work includes supply, operation and maintenance of buses and charging infrastructure. In outright purchase, the bidder could quote the fixed sum to be paid as per delivery schedule whereas in GCC the bidder has to quote service charge as rupees per kilometre basis.

Since electric buses are a new technology and STUs did not have the adequate expertise for operations, they preferred the GCC model and allocated all risks including technology and operational risk to the operator or OEM. The decision to limit the business model to GCC in the second phase was taken based on previous experience. The trepidation towards electric bus technology in Indian market led to risk allocation tilted towards bidders and hence limiting the business model option to GCC.

Conditions of FAME

Under the FAME scheme, the cities upon allocation of buses under the scheme to them are required to issue a tender for the selection of operators for supply, operation and maintenance of electric buses under GCC. The tender usually includes several segments of information including scope of work, terms of procurement, obligations of different entities, payment conditions, implementation conditions, etc. The contents of the tender document can be segregated into three parts namely i.e. request for proposal (RFP), model concessionaire agreement (MCA) and technical specifications of the bus.

The RFP includes letter of invitation to bidders, definitions and abbreviation details, information to bidders, qualification requirements, etc. The invitation section includes work scope, timeline of bidding process and authority detail for clarification. The RFP issued by Chandigarh City Bus Services Society, Chandigarh is taken as reference for understanding of the contents (4). The definition part includes the context or meaning of abbreviation and important terms. The information to bidder includes the technical and financial requirements for bidders. As in the Chandigarh tender, the bidder should have supplied 20 electric buses in the past five years.

The composition of consortium, disqualification criteria, bid security details and documents required for bidding are all part of it. The evaluation criteria and price bid format are part of RFP. Based on the rates quoted by bidders, one with the lowest cost is awarded work. This is known as the L1 system where the lowest cost quoted during tendering process is selected. The MCA comprises 42 articles and schedules covering the procurement, payment conditions, obligations and implementation aspects. NITI Aayog had issued MCA for electric buses in India on OPEX basis for reference (5). The duration of contract includes fixed term, add on years and criteria. The cities can modify it as per their requirement.

Certain Case Studies

In the recently floated tender by Convergent Energy Services Limited (CESL), the contract period included vehicle utilisation of 10,00,000 km in addition to the number of years (6). The penalty for late delivery and conditions precedent including the penalty payable is part of MCA. The payment conditions including assured kilometres i.e. guaranteed kilometres travelled by a bus either monthly or annually, payment conditions, fee revision, etc. The NITI Aayog has suggested fee revision based on inflation, but some cities have opted for fixed fee escalation e.g., Bangalore.

To allocate the risk, the obligations of authority and bidders are defined in the MCA. Similarly, the key performance indicators (KPI) of bus operations, penalties due to non-adherence to baseline values of KPI, ownership of assets at the end of contract, payment due to termination etc. are all parts of the MCA. The bus specifications include general design specifications, technical specifications and compliance requirements. The general specifications include functional requirements of electric buses from electric proposal systems to doors. The technical bus specifications include vehicle dimensions, maximum speed, gradeability, angle of approach, seating capacity, etc.

The CESL tender even mentioned battery life and lifetime warranty for the battery, electric motor and controller in the bus specifications’ segment. The compliance requirement includes Central Motor Vehicle Rules (CMVR), Urban Bus Specification II, AIS 140, etc. As per UITP report on electric bus procurement, similarity and dissimilarity amongst cities can be noticed on various parameters (7). More than 20 parameters were used to compare the tenders floated by more than 20 cities. The parameters identified were buses tendered, GCC rate, assured kilometres, responsibility of electricity payment, method of fee escalation, termination conditions, etc.

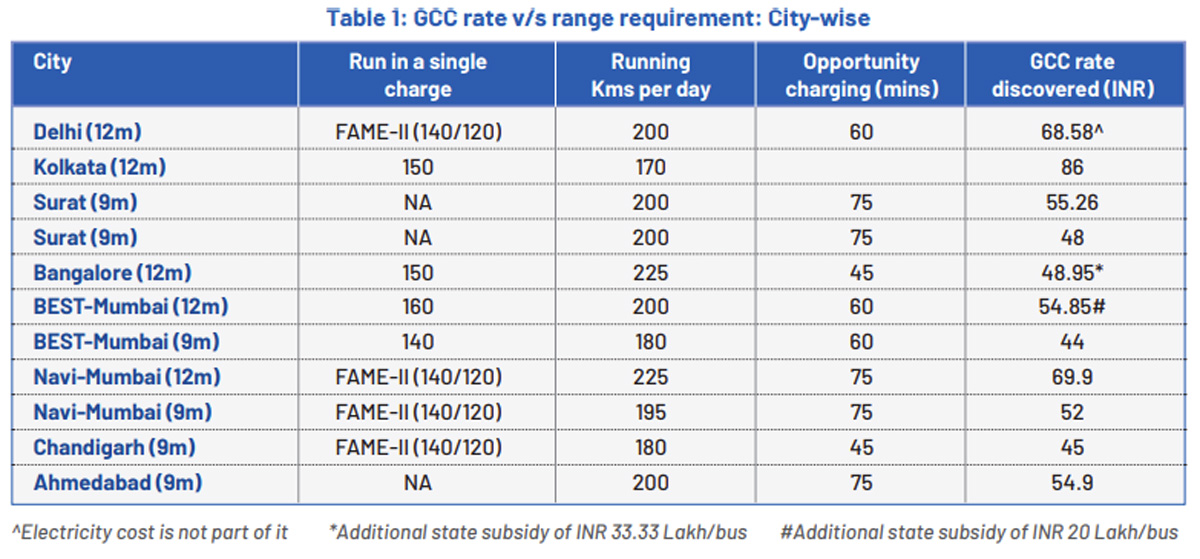

Most of the cities kept contract duration of 10 years and majority of buses tendered were of nine metres in length. In terms of vehicle utilisation, the assured kilometres differ based on bus length and city requirement. The considerable variation was observed with minimum value of 4,200 km per month to 6,600 km per month for urban operations and even went up to 18,000 km per month for inter-city operations. One of the key trends observed in all these tenders is the range requirement i.e. run in a single charge being around 160 km or even lesser. It is not that bus utilisation i.e. distance travelled by bus per day for Indian cities is lower than the range requirement.

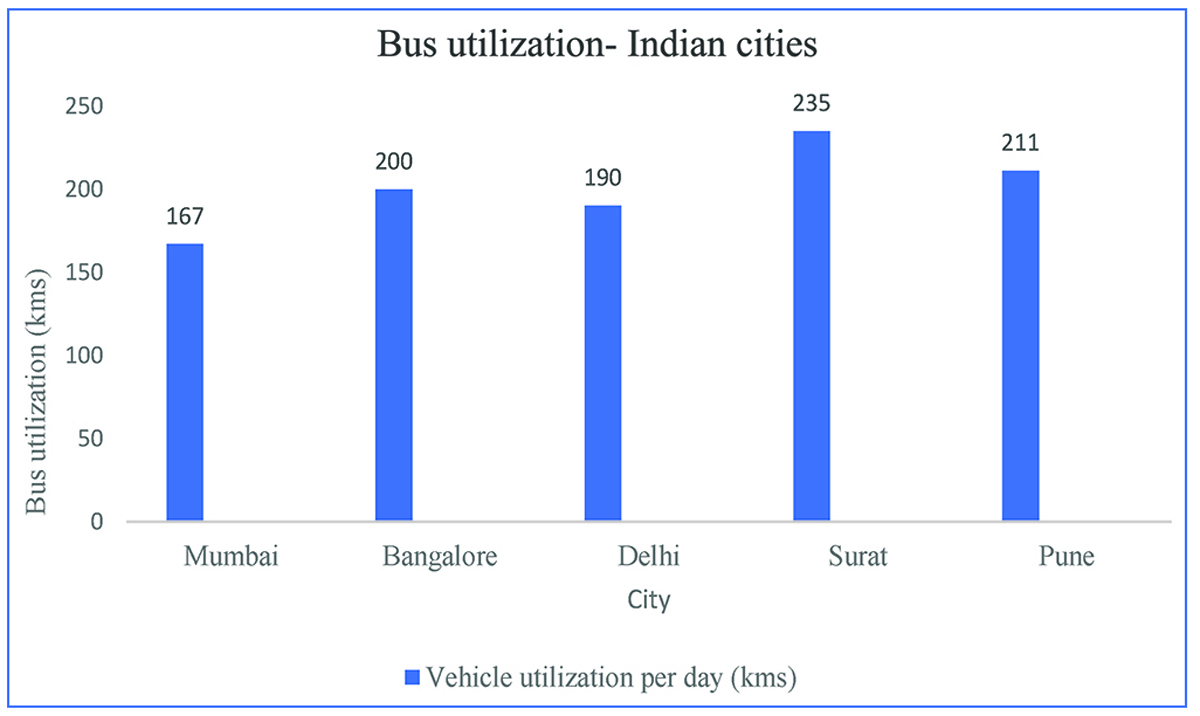

As per the Central Institute for Road Transport (CIRT) report on STU performance in 2017-18, the average bus utilisation for urban region is 236 km. The average vehicle utilisation per day for major cities who are also part of the recently launched grand challenge is shown below (8,9):

Some cities included higher range requirement in the initial phase of tendering but reduced it to lower value during the later part of tendering process. Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply and Transport (BEST) in their tender released last year had range requirement of 200 km which was reduced to 160 km, utilising 80% state of charge. Similarly, Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) floated a tender with range requirement of 200 km but had to cancel it couple of times as the gross cost contract (GCC) rates received were higher than anticipated.

The lower range requirement coupled with opportunity charging availability is fulfilling the vehicle utilisation in a day.

This condition will lead to two scenarios. The first one is to replace electric buses with conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) buses with flexibility to run them on any routes. This might lead to replacement ratio greater than one and force operators to deploy more buses to maintain the desired service level, and eventually lead to higher GCC rates. The second scenario might be to reduce the flexibility in operations by specifying the routes for electric buses’ operation. At present, the latter option is a win-win situation for both city authorities as well as operators.

Range Requirement and Vehicle Utilisation

The table below shows the GCC rate achieved in recent tenders along with range requirement and vehicle utilisation. None of the cities in the table below have been running kilometre requirements per day equivalent to run in a single charge. The running kilometres requirement is achieved with making available the option of opportunity charging. Surat tender with GCC price of Rs 48 per km and Chandigarh tender are the latest ones. As part of UITP India’s ongoing project, the information from the recently floated tender document for supply and operation of electric buses is collated and shown below in Table 1.

Convergent Energy Services Limited (CESL) is spearheading the second phase of FAME II scheme by aggregating the electric bus demand across nine cities with population of more than 4+ million. They have aggregated the demand of 5,450 buses spreading across Delhi, Kolkata, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Surat (10). Considering the issues faced by authorities regarding range requirement in the previous tender, CESL in their tender have the necessary range requirement of 250 km for 12 metres and 225 km for 9 metres for fully charged battery. This will give more freedom to authorities for operating electric buses on multiple routes. On similar lines, BEST in their latest tender have also mentioned an operating range of 250 km in single charge utilising 100% state of charge (11).

Delhi Integrated Multi-Modal Transit System (DIMTS) have also included a minimum range of 200 km in a single charge throughout its lifecycle (12). These are positive developments for the public as well as private bus operators as they would help to overcome the vehicle utilisation issue that currently authorities are facing. This will further help towards a more matured electric bus market in India. The development of higher driving range electric bus will create conducive environment for deployment of buses on longer routes and develop the electrification inter-city bus market. It will reinforce the Government of India commitment towards EV30@2030 (13). To achieve this target, the EV penetration should be 40% for buses which would be difficult to achieve with present driving range of electric buses.